Point Guardian, ok.

Looking at what I’d about to write, I have a fear I’ll be too rough. But this is a very ambitious comic, it seems, and author also seems to have in mind a professional career. He seems very devoted to this comic, aiming to develop it into a legacy, a kind of wide panoramic world such as the one of X-men, for instance. But if the comic has a problem, it’s not something you might justify as “well, it’s just a hobby”, not for this comic, I think.

It’s a classical superhero comic, meaning that it relies heavily on stereotypes of golden-age marvel and DC comics, so far that author admittedly makes some characters hommages of old Marvel characters. It’s not common to find that in Superhero nowadays, mostly superhero comics try to be revisionist in putting superhero comics in a realistic setting and rationalizing them into something that can be believable. Either that or they go for camp, anknowledging flakiness of original but looking at it as a mix of nostalgia and mockery. Here’s a comic that goes for straight-faced, serious return to old superhero concept. I’m wondering whether it’s a good approach at all, I always thought that the view of old superheroes as campy icons nowadays, is a sign that comic audience matured, and what this comic does is expecting that it doesn’t – that the world is as naively open-minded as in 40ies and 50ies. But it’s not, both in scientific and moral issues. I don’t think that the concept of a guy who gets superpowers by being struck by a thunder, nowadays, works, except in a campy setting, which this comic is not.

Really the only element of revision is the lack of smartass quips that was trademark for superheroes back then. So, no Spiderman saying something witty while kicking the villain, thank god. Instead, dialogues are much more leveled and timed, which means that you won’t hear a character heavily monologuing in a scene that supposedly happens in a bit of second. So from that side, comic is improvement of the concept.

What it does accept from its influences is awful simplification of moral issues. The reason why many people started revising Superheroes was, I think, that possibilities of inner research of moral questions were left blatantly unexplored back in early days. Here we have a comic that takes over the old scheme; sort of moral mapping, where we have good guys who are infinitely good and bad guys who are infinitely bad, and then we have a few shady guys thrown into the good guys, for good measure, to give it air of moral ambiguity. But you can see what I’m talking about simplification of moral issues in scenes where relationship between main characters and government is explored. As naïve as good will and collaboration of them is at the beginning, as is the later development where government tries to control superheroes and superheroes are “righteously” indignant. But comic’s tone never seriously questions righteousness of heroes, their motives or their right to do what they do. Just think:

http://www.pointguardian.com/d/20051212.html he’s not comfortable with authorities knowing where he is. It’s never a question whether common people are comfortable with having such power going around controlled by just one person’s judgment.

There’s a line of thought that relates this approach back in golden age with political air of the times, what with the idea of someone mightier than you to whom you are supposed to infinitely trust and be thankful. It’s notable to mention than many of great authors of the time were extreme conservatives, and I’m only mentioning for one reason: to warn you that when you accept their concept, you implicitly accept political opinions that they’ve built into their comics, whether you realize it or not. Today, I think, average reader is not as open as before, to enjoy a story on its superficial level and not to question it’s implications, be them political or moral.

As far as I’m criticizing I’d like to note a few things about designs of characters. First one is that Ultra, the main character, with his concept, absolutely doesn’t deserve that position. He might be the blandest and uninteresting superhero character in the comic; asides from his goody-two-shoes nature, his powers are pretty much nothing interesting. I have a hard time actually remembering what they are; the only thing I know is that he’s supposed to be more powerful than the rest. But as to extent lack of inspiration in his concept, there’s design; just take a look at his signature letter, it looks more like a logo of building company than a sign of superhero; it’s static and closed shape, while I assume superhero would rather choose something dynamic, something that emphasizes movement and power. As to support this, the comic isn’t even based on him, even though he’s either central character or important paternal figure all through the comic.

The other character I have a problem with is Divine, an angel all with aura above her head. Simply said, pathos. Though I can imagine that author was proud with this concept, it goes to show that Faulkner’s assessment that writers should “kill their own favourite babies” was true. No matter how hard it is to discard them, sometimes ideas that you’re most proud of are the ones that don’t fit into the entire thing, either that or they work well only in your head.

But I may be being too tough on this now, so for what it’s worth, I think that writing is up to standards of the ones it looks up. I seriously don’t think that writing of PG is any worse (it’s even better) than anything Stan Lee ever wrote. I just happen to think that it’s not a hard task at all. PG brings an interesting sub-storyline in introducing so-called children of main superheroes and as these characters appear to be troubled and unsure of themselves, unlike their parents, they turn out to be much more interesting than their parents. As usual, comic is better when it talks about ordinary lives of superheroes and how they deal with their situation, and less interesting when it indulges into lengthy action scenes. Action scenes would actually probably be much better if the art was better. On top of my head, I can think of this (

http://www.pointguardian.com/d/20050125.html) scene; short, efficient and clever. Too bad, camera angles and poses make it look like everything happened in a span of few minutes, not in a matter of seconds.

Ironically, despite the conventional content, art would belong to some art-brute underground magazine rather than to mainstream comic books. Author does a lot of experimenting in inking field, changing tools often and advancing some in that field; it’s not surprise when you read that Jack Kirby is one of his main influences as it’s evident in the way he tries to use a brush, however, Kirby was anything but sloppy, and inking of this comic often is. There’s still lack of control over thickness of line, even though artist does a n effort to overcome it.

But the greatest surprise about art is how long the comic went without any improvement in pencil department. It seems like only recently author took some practice of anatomy, a bit strange for a superhero comic.

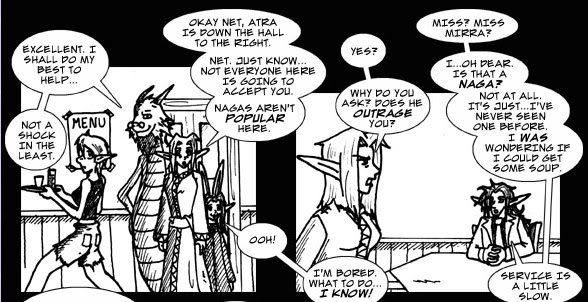

Art is very simplified, often, pages contain only bare necessities for conveying a story. You can see this on faces – they contain basic facial features necessary for recognizing characters, but nothing in department of shading or more subtle face lines, nothing that would flesh out emotion or mood on them.

There’s some use of screentones of which I approve, because it’s used functionally and rationally, usually to support the page (not to dominate it) and to give it a sort of abstract aura. The most interesting pages are the ones where author uses tricks with inking tools so represent some more or less abstract imagery. Like this one:

http://www.pointguardian.com/d/20070209.html

In brief period when comic was coloured, colour was giving good results, helping unify elements that otherwise sometimes feel disjointed, and, overall supporting the mood.

Back when Keff reviewed me, she suggested that I should slow down and take my time with pages in order to get better results. Struggling whether to give advice that I myself don’t hold to, I still have to suggest that you do the same. Pro authors like quoting Herman Hypen who said, I think, that the first time he started drawing professionally was when he slaved over a single page for a month, and then somewhere during that month, he crossed the line between amateurish and professional, and later found that this line isn’t hard to cross once you manage it. That means that you learn more from executing one well-done page than from executing ten sloppy and half-finished pages.

Comic has commendable updating tempo of five days a week, for years without missing an update (except for some fillers here and there), but you have to decide what the priority is: telling more of the story or developing artistically.